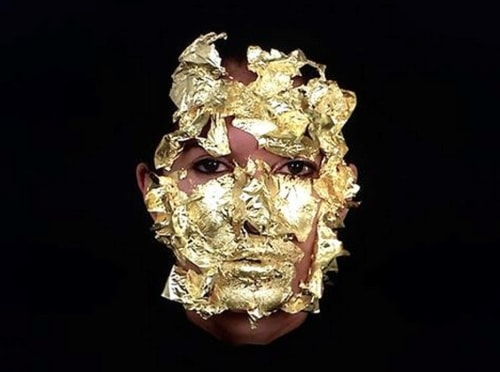

Golden Mask, Marina Abramovic video from 2010 explores the artist as icon, sidled alongside ancient civilisation's use of the mask and gold. Photo ArtsHub; courtesy the artist.

For Marina Abramović's first exhibition, at age twelve, she painted her dreams. ‘I believe in everything,’ she told an audience at a sell-out conversation with David Walsh, founder of Hobart’s Museum of New and Old Art (MONA).

Walsh’s response was anything but flowery: ‘And I don’t believe anything.’

Walsh’s investment in Private Archaeology - Abramović most significant solo exhibition in Australia which opened last weekend - is a curious choice given his scepticism. The MONA founder who is known for his anti-spiritualism, is promoting an artist who believes in the power of crystals, the energy of objects, and the transformative nature of ritualistic performance or actions.

MONA has been a self-declared secular temple guided by David Walsh’s commitment to the scientific method. Even his car parking space is labelled 'God'.

But Abramović is pushing Walsh’s boundaries. The artist - who prefers to be referred to as a ‘warrior’ than the sticky title “grandmother of performance art”, which she loathes - said her art grew out of her awareness of the non-physical world.

‘I never played as a child with dolls. I played with the shadows and the invisible people I see. Then I went on to the clouds, and then to performance.’

She acknowledges the clash between her worldview and Walsh's, clearly unfazed.

‘It makes my balls shrivel, is what I said,’ corrected Walsh.

Despite - or perhaps because of - the tension, there is a rapport and trust between artist and collector, which has allowed Walsh and Abramović to collaborate to present important new work.

For Power Objects (2015), commissioned by MONA, Abramović selected pieces from Walsh’s collection of antiquities based on their inherent energy and use in religious ceremonies. The objects are paired with a performed video Cleaning the Mirror III (1995), where Abramović moved her hands over objects from the permanent collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (UK), gauging their spirit of good or evil.

Also presented in the installation was the photograph Places of Power (2015) in which Abramović cups her hands around a small Brazilian statuette, a gesture that revers its ancient power. The implication that Abramović has the ability to draw out connections other than the physical flies in the face of Walsh stated philosophy that these objects are only objects.

Walsh admitted his resistance to Abramović's work. He did not participate in the artist is present, her now iconic work at the New York exhibition at Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2012, where audience members took turns sitting opposite Abramović.

‘I just can’t imagine how I could do that; I am a rationalist, a reductionist,’ said Walsh. ‘The way I get self-awareness, I think, is not by turning myself off. I find it in incredible things – those with a spiritual bent would call it magical reality – when I walk into the room in the gallery, where the body is confronted with the energy (of an artwork). I have no connection with it at a spiritual level - that it is aesthetically completely profound for me. I feel like I am getting something from it but not understanding where it is coming from.’

Abramović's take on the mystic is almost the opposite.

‘For me was really going to nature, to indigenous cultures such as the Tibetan, Aboriginal culture – people don’t understand how much that influenced my life. These people have some ancient knowledge that I can really work with that with the body,’ she said.

Abramović has studied Brazilian shamanism and believes in the importance of our engagement with nature, and the healing power of crystals and gems on the human body and mind, according to a gallery statement.

Two large galleries have been handed over to the installation Transitory Objects – or more colloquially the crystal rooms – artworks using obsidian, quartz, hematite, amethyst geod and performance.

‘I don’t make sculptures. I don’t believe in sculptures, especially in nature,’ Abramović said. Rather these objects – like Walsh’s antiquities – are used as a kind of pawn or talisman for triggering a physical and mental experience, but in this case it is to the public.

Here she encourages you to touch the art.

This audience directed engagement holds a strong thread across Private Archaeology, with the inclusion of Abramović well-know work Counting the Rice, the two pieces mentioned Transitory Objects and Power Objects and another new work, The Chamber of Silence (2015), where visitors are invited to sit with noise-cancelling headphones and disconnect and reconnect.

Walsh’s response was in character: ‘Do you want to change people who are sceptics like me, is that part of the process?’

‘I really want to see how I can change my consciousness about things and by changing mine I can influence others,’ answered Abramović.

‘We sit in our comfortable chairs and we criticise…it’s really important for an artist not to just reflect how society looks today - we know how it looks – it is not important what is the solution. What I am proposing is go back to simplicity. It is not that technology that is wrong; it is our approach to technology. It has taken all our time. I am changing consciousness and asking you to see what you can do with it; what you can do in your private way, to lift human spirit is important. It is a huge collective work,’ she added.

Abramović proposition in the simple exercise of counting rice is a demonstration how you can take this theory into your own life. Stripping oneself of all belonging and donning on a lab-coat, one commits to the kind of alchemic transformation … or for those sceptics a box tick of having “done a Marina”.

For the less committed, another participatory work that invites a meditative viewer engagement is Waterfall (2003), seated confronting the individual chants of 108 male and female Buddhist monks that were recorded over a five-year period.

It sits as a stunning transition from The Chamber of Silence and has an odd connectivity to Abramović’s earlier screaming videos, three of which are presented in the exhibition that explore human energy and a kind of catharsis and life force through physical action.

Walsh observed of these pieces: ‘You seem to get same effect, the same engagement, the same internalisation from screaming and from being completely silent. It seems whatever the engagement is it’s not relevant, it is just that moment of pathos.’

He asked Abramović: ‘Is the scream room meant to be uplifting? I don’t feel uplifted; I feel challenged, threatened.’

‘It’s liberating; it is energy. You can scream for energy or you can scream just for the scream it is good,’ she said.

Walsh: ‘I’m not much of a screamer.’

‘I always do things I am afraid of; I don’t things that are easy, because doing easy things your mind can never change. It is always the same,’ Abramović continued. ‘You push your mental and physical space – that is really interesting for me.’

Walsh has always pushed the boundaries, like Marina, in his own way, perhaps that is why this skeptic and believer respect each other.

He continued: ‘I am trying to capture here “the Marina moment”. Whenever I think of you I always have that Christian metaphor in my mind – you are an absorber of pain, of doubt? Do you dream up works of art? Is it intellectual or purely emotional?’

‘For me they come unexpected almost like a hologram in space,’ Abramović answered. ‘I immediately take away the ideas that are nice. These are not good ideas because they’re too easy. I always think of ideas where I become obsessional because I am afraid of that.

Abramović credits her time in the Western Desert with the Pitjantjatjara and Pintupi Aboriginal people (1980-81) as a moment of discovering “mindfulness”, when the conversation moved from the verbal to the telepathic.

‘The most important thing for me of that experience is this idea of here and now. These people don’t have past and future, it is the present this is the only reality that we have.

‘Performance is not in past of present - it is in the now.’