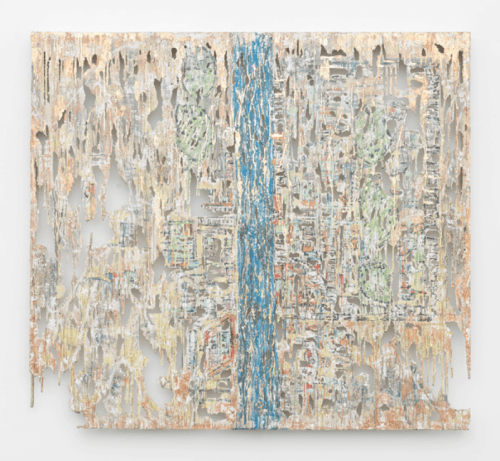

Diana Al-Hadid, Split Stream, 2017. Polymer gypsum, fiberglass, steel, plaster, pigment, tape, gold and copper leaf, 58 × 64 × 3 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Diana Al-Hadid. Photo: Object Studies.

In the Islamic Golden Age, Turkish engineer Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari wrote a proto-Borgesian text called The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206). This 13th-century collec- tion of fantastical engineering projects detailed, in straightforward language, instructions for creating fountains, automatic hand tools, timekeeping de- vices, and self-playing musical instruments. When contemporary sculptor Diana Al-Hadid came across these brilliant, poetic, and functional contraptions, she was galvanized to work towards new ways of working with space, physics, and materials in her own practice.

Diana Al-Hadid was born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1981, and moved to Canton, Ohio, with her parents when she was five. While studying sculpture, she developed a style steeped in classical references, with particular influence from the Old Masters. Incorporating themes of antiquity and architecture into intricate, figurative tableaux, her work is distinctive for its simultaneous complexity and seeming weightlessness. She works with a repertoire of sculptural techniques—structurally reinforced white plaster “drips,” exposed armatures of tarnished rebar, fancifully modeled representational objects, such as buildings and figures—that give the appearance of timeworn decomposition. When there is any color in her works, it tends toward neutral, lighter hues, as if aged. In 2010, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles hosted her installation Water Thief, a full-scale, non-functioning water clock. It was her first foray into exploring Al-Jazari’s timepieces. With her new exhibition, Falcon’s Fortress at Marianne Boesky Gallery, Al-Hadid has again taken on Al-Jazari’s man- tle. Inspired by the innovative spirit of Arabic wisdom from the 8th to 13th centuries CE, Al-Hadid’s latest offering provides rich insight into her evolving creative process as she reconnects with her geographical and cultural origins.

In The Candle Clock of the Swordsman (2017), a seven-foot tall copper and brass armature is coated with a torrent of hardened candle drips. Beneath the armature is an elaborate matrix of chutes carrying ball bearings, which borrows its design from one of the candle clocks described in Al-Jazari’s book. An early method of measuring time, candle clocks marked the passage of hours through the use of a burning candle connected to a counterweight via a pulley, which rose as the flame consumed the candle. The movement resulted in the periodic release of ball bearings that collected along a channel to indicate the hours. Al-Hadid was faithful to Al-Jazari’s design, even including a decorative gilded falcon at its center-point. With outspread wings, it emits the ball bearings from an opening in its beak. However, in its idiosyncratic details, such as the exaggerated excess of melted wax, the sculpture is also a space of play for Al-Hadid’s material explorations. The “wax” is, in actuality, a plaster blend of Al-Hadid’s own concoction. Hazily iridescent clouding, remnants of the welding process, lend a rustic and distressed patina to the frame’s metallic surface. The overall effect is as though the piece was unearthed from an architectural dig, with wax accumulated at its base, as if it remained functioning for centuries. While the sculpture no longer keeps time, its machinery rendered inoperable by Al-Hadid’s aesthetic flourishes, it did briefly work. As a tribute to the early astronomers and cosmic time-trackers of the Islamic Golden Age, Al-Hadid ceremoniously dedicated its only run to this year’s solar eclipse.The falcon motif recurs throughout the exhibition, appearing in two additional sculptures—The Candle Clock of the Scribe (2017) and The Candle Clock in the Citadel (2017)—as well as in The Falcon in the Mirage (2017), a polymer-gypsum wall panel. In this sculpture, a resting falcon is perched within an oval vignette, superimposed over an aerial view of inverted palm trees. Like the other wall panels in Falcon’s Fortress, it bursts with vivid, shimmering copper surfaces.

Most of the panels in Falcon’s Fortress took inspiration from the 16th-century Ottoman illustrated manuscript, Menazilname. Its author, Matrakçi Nasuh, was a Bosnian mathematician, geographer, calligrapher, polyglot, man of arms, and miniaturist. Menazilname documented Nasuh’s time as an infantryman on a military campaign, during which he painted the locations of his army’s encampments and major cities along the expedition’s route. While leafing through a modern reproduction of this text, Al-Hadid recognized a familiar visage: the Citadel of Aleppo, painted in Nasuh’s meticulous hand. Damaged but still standing today, the Citadel is nearly identical to how Nasuh saw it hundreds of years ago, even after Syria’s devastating civil war. In Falconer’s Fortress, it reappears in two untitled drawings on Mylar, but its form can be made out more clearly in a third work, a large polymer-gypsum wall panel. The Citadel is depicted on the left, nestled into a bustling urban landscape. The work is titled Home Base (2017); in this expression, Al-Hadid acknowledges a debt of gratitude to her heritage. It is not only an homage to Nasuh, but also to Aleppo, its fortitude and longevity.