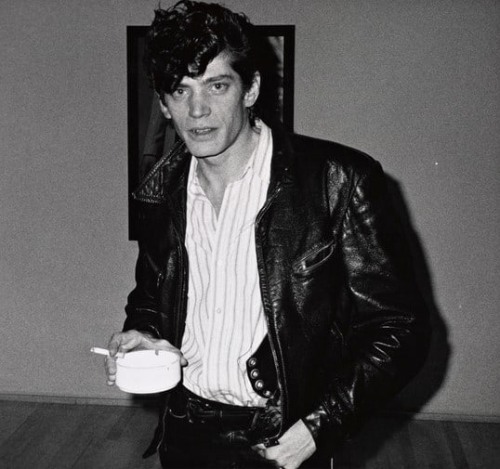

Robert Mapplethorpe in a photograph from about 1981. Credit Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Twenty-five years ago this month, a Cincinnati jury wrote an exclamation point into the story of the culture wars that were raging through art museums and academia. The jury acquitted that city’s Contemporary Arts Center and its director of criminal obscenity charges for exhibiting a group of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, graphic sexual images that became a watershed in debates about what constituted art, what kinds of art should be supported by government money and who should have the power to decide such questions.

Among the handful of these images carried through the halls of Congress by Senator Jesse Helms — the standard-bearer opponent of taxpayer support for what he called “filthy art” — was “Man in Polyester Suit”: a tightly cropped picture of the torso of a black man wearing a three-piece suit, with his large penis hanging out, like a Montgomery Ward catalog hacked by Tom of Finland, with an assist from Duchamp and Groucho Marx.

That photograph, made in 1980, just before the AIDS crisis exploded, was not one of the seven that generated the obscenity charges. But in the years since the case, it has come to be regarded as perhaps the most important picture from the show, as well as Mapplethorpe’s most slyly powerful work, a deadpan commentary on race, class, sexual stereotypes and the slippery nature of photography itself that continues to jangle nerves in ways that his overt S-and-M pictures never quite did.

On Wednesday, a print of the work will be auctioned by Sotheby’s, the first time in 23 years that any of the 15 prints from the edition have come up for public sale. The auction and a Mapplethorpe retrospective that will feature the image, opening next year at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, are returning “Polyester Suit” to the spotlight for a kind of victory lap, and in the process are raising questions about whether images still have the same kind of ability to unsettle and provoke.

“I think it’s still one of the images that would draw attention and make people very uncomfortable, even 25 years later,” said Dennis Barrie, who was the director of the Contemporary Arts Center at the time of the trial and who could have served prison time if the verdict had gone the other way. “It’s this complex message about race and black men and black power and black sexuality that really got to Helms and some of the other opponents.” When William F. Buckley Jr. traveled to Cincinnati to see the exhibition, Mr. Barrie recalled, “he came back out of the galleries, and he specifically mentioned ‘Man in Polyester Suit’ when he told me that it was a beautiful show, except for about 15 pictures. And I said, ‘Well, we’re only being indicted for seven.’ ”

Joshua Holdeman, Sotheby’s worldwide head of 20th-century design, photographs and prints, said: “I think the issues that are at play with this image are still very much happening today. It’s not like race is off the table.” It might be partly for those reasons that public institutions have tended to shy away from the picture. Only three prints are in museum collections — one shared by the Getty and the Los Angeles County Museum; one at the Guggenheim; and the third at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; the image that is to be auctioned has been owned for more than 20 years by a collector in Amsterdam who has chosen to remain anonymous. (Most news organizations, like this one, will still not publish the picture, and Mr. Holdeman said that even now it probably could not be used on an auction catalog’s cover.)

The print’s estimate is $250,000 to $350,000. The last time this print sold at auction, in April 1992, while the controversy surrounding it was still relatively fresh, its estimate was $3,000 to $5,000, and it sold for $9,900, according to Christopher Mahoney, senior vice president of Sotheby’s department of photographs.

The most expensive Mapplethorpe to change hands at auction so far is a portrait of Andy Warhol that sold for $643,200 at Christie’s in 2006 (about $760,000 today). But none of the photographs from what are known as the X and Z Portfolios — the explicit sexual images and classicized, mostly nude, portraits of black men — have drawn the kind of price estimated for “Polyester Suit,” which means that if it meets or exceeds expectations, the market for Mapplethorpe’s work could accelerate more broadly.

“I think everybody who owns this particular work knows how important it is, and none of them want to let go of it — it’s not been a work that anyone has bought to hold for just a few years,” Mr. Holdeman said. “I think of it as his most conceptual piece. You either have to write an 800-page dissertation about it, or you have to look at it as a kind of perfect joke and laugh. It works on so many levels, and there’s still so much going on in it.”

Puryear in a Park

Next May, Martin Puryear’s largest sculpture to date, 40 feet high, 38 feet across and 10 feet deep, will command Madison Square Park in New York like a kind of Trojan horse. Known for his allusive abstract works that fuse organic and geometric forms, Mr. Puryear will employ rough-hewed versions of his signature materials that nod to urban life. A model of the piece, “Big Bling,” shows a plywood grid, with a curvilinear outline suggestive of an animal’s silhouette, and an amoeboid shape cut out of the interior. Its plywood tiers will be wrapped in chain-link fencing. “It becomes a barrier — people can’t ascend,” said Brooke Kamin Rapaport, senior curator at the Madison Square Park Conservancy, which commissioned Mr. Puryear, 74. The work will be crowned by bling: a bright gold shackle, “a beacon that you can either say adorns or restrains,” Ms. Rapaport said — depending on your New York story.